Harbour Politics, Binchi and an Immortal Mackeral. October-April 2024.

As the late autumn winds arrived carrying waves from brewing storms across the Atlanic, we were immensely grateful to be bobbing safely in Port Rhu, It hadn’t been easy getting a place, and the anchorage was getting more wild with every day that crept towards winter.

Within the first cold weeks we found 12 bags of wood pellets in the bins at SuperU, which kept us cosy, but didn’t come without a price. Due to the damp and density of the pellets, the smoke would build up inside the stove before exploding and sending the oven lid, smoke and sparks through the boat with one of us close behind patting out embers with a tea towel. Everyone else seems to heat with electricity. One evening our neighbour proudly showed us his four different heaters, unfortunately the electricitry trips out multiple times a day, and you often hear him swearing late at night in the rain, putting the fuses back in. The mast, bound tightly in fairylights would then light up like a neon Jesus, flashing through the night. He also likes leaving the postion lights and anchor light on as he finds that they look nice.

There is a love-hate relationship between the boat dwellers on this side of town, and the harbour office on the other. It was unbelievably complicated to get a monthly contract, but very easy for us to stay and pay a daily price. The toilets are an absolute disgrace, and the price of the harbour is going up, yearly, forcing away travellers and sailors who make a lifestyle out of it, and making space instead for moored up yachts sailed only a few times a year, their owners living in Paris and other expensive cities are barely affected. Maritime people with their culture and creativity become less, and the harbour becomes quieter, and ‘cleaner’, and easier for the council to manage.

Over the five months spent on that pontoon we shared picnics and music, celebrated birthdays, had waterfights, climbed over piles of lego with bicycles and swapped stories and dreams and tools.

There were many late-night-pop-up supermarkets with the discarded treasures from Intermarche and SuperU, piles of cakes and croissants, salads, cheeses, sheeps yogurt, aubergines, herbs and salmon, and always hundreds of bananas. One saturday our neighbour brought home a 10 kilo bin bag of king prawns.

For the whole week the smoke and steam of grilled shellfish came puffing out of his boat along the harbour, attracting the 8 cats that him and his family had brought. They had 2 dogs, and 3 children on board who shared in the glory of dumpster diving with us, eating cream cakes and pain-au-chocolat straight from the bin. We had no shame and lived like kings.

After the ‘Grande Tempete on the 1st of November he turned up with 20 frozen pies and 5 litres of doughnut jam that had been thrown out of the bakeries that lost electricity over those stormy days. Roofs blew off, a boat broke free and drifted out to sea, and our boat leered drunkley sideways with every gale that whistled loudly through the bridge and down to the sea. A gale of 207kph was recorded around the corner at Point Du Raz, and the strongest wind ever recorded in Brest was that night.

The following day I drove with Constanze and some friends to see the waves. After climbing the big rocks on the cliffs edge, you could lean your body into the wind and be held, as the sea spat foam up from the crashing waves 30 metres below.

We still have some of that jam, its never been in the fridge and shows no signs of spoiling which is quite worrying.

In October Niels parents visited for a week, delivering us 40 kilos of dried food that we ordered from DM as the prices here are extortionate. Together we went to markets, drank cider, played games and walked along the coastline at low tide collecting edible seaweed and soaking up the last of the warm autumn days.

Our last sail of the year was during this time, and it was quite adventurous. The sun shone brightly but did absolutely nothing to warm our cold bones as the wind tore straight through our wooly jumpers. The sea was a little rough and our queasiness wasn’t helped by the dead dolphin we sailed past, or the immortal mackeral we then caught. It was a bloodbath, and after returning from the dead 20 minutes later despite barely having a head, no one had much appetite left. C’est toujours pareil.

Most of our friends were met through music, converstaions began while I was busking and Niels would network. Angel was at one market, and Lou at another. She introduced us to some social spaces, events and workshops, and with Lou a singing group started at La Roche, a big house project on the cliffs.

Food and wine, songs and stories were shared around kitchen tables and fires, up trees and in the sea.

We were invited to our first Fest Noz – a traditional Breton dance night – and Angel did her best to teach us the dances. The rest of our friends were made through sharing the gifts of the boat. Niels was busied making sourdough breads and oatmilk for our friends and neighbours, and I contributed Binchi – which is Kimchi – but using only ingredients that were found in supermarket bins.

Once, on a grey day in early February, 7 or 8 of us went skinny dipping when a busload of elderly tourists in high vis jackets appeared. They were quite a spectacle, although they probably thought the same of us. Constanze and I tried to swim as often as our courage would allow, and sit afterwards, shivering on the wall smoking cigerettes and burning our cold mouths on hot chocolate from her green flask.

Not drinking coffee in France was a constant source of embarrasment for Niels and I, though not nearly as embarrasing as drinking a ‘Bloody Lairy’ which can only be ordered in seperate parts and mixed in private, or ideally, ordered by someone else. La Calle is an Irish bar at Rosmeur which has live acoustic music on every other friday, and the mix of fiddle and an Irish-French accent is quite magnifique. During a stirring and quite long rendition of Dirty Old Town, it was born, the Bloody Lairy, a cocktail like a bloody mary but with whiskey instead of vodka. Smokey, spicy, and disgraceful, it became a thing of local legend (or so we hope) and we dressed as its ingredients for Les Gras, a carnival that engulfs the town with samba, expensive beers, and a combination of wierd, wonderful, and sometimes very dissapointing costumes.

We left Douarnenez for over a month for some work in Germany, Niels was doing stage tech for a theatre company in Leipzig, and I was cooking for the childrens circus in Sohland. We then spent 2 weeks working on a boat deck in Flensburg before embarking on the 37 hour journey home to Atlanta. It was only once I’d left France that I realised how unique and wholesome our winter had been. It wasn’t all smoothies and sourdough though, there were also low times. It rained allot, allot allot. For days I wouldn’t leave the boat except to use the disgraceful toilets. Niels was working at a boat yard but was entirely unmotivated and on his own allot for the project. It was badly planned and he was stressed. All his worries came back home with him, spilling out into our tiny space in the dark evenings, making it feel even smaller and darker. While sailing we were constantly occupied by the day to day, getting to the next place, eating, sleeping, being outside in the sun and rain, and it was a shock to the system to be still. I felt pretty lost.

Slowly however, spring was creeping in at the edges. On my birthday it was a calm night and we had a barbeque on a half-island, grilling tofu, peppers and aubergines, and introducing ‘stick bread’ to the French. We had picnics on the sunny pontoon with duvets to keep warm, and Niels and I went on some long cycles- to the scrap yard and to Lidl, it was very romantic. I spent allot of time sewing and dying fabric with traditional sail dyes, scraps of fabric in shades of earthy reds and browns hung fluttering along our railing ready to be screen printed and sewn into bags

By the time we got back from Germany, I was expecting full blown tropical springtime, but I was completely wrong. It rained non-stop and it was cold.

Then, on the first of April we woke to a loud scraping crunching sound followed by shouting. The neighbour had reversed into us. Reverse gear had got stuck in- not for the first time- and they just powered on, unable to stop revving. Our ladder was ripped straight off, the solar panels scratched and the frame at the back of the boat with the wind steering was bent inwards. A few days later, without paying us or the harbour or even telling their friends, the whole family and two dogs dissapeared into the night on their boat, in a storm. They were rescued the following morning by coastguards after “cruising” 6 metre waves all night, proudly telling everyone that they were ‘just practicing sailing’.

It was hard to start doing repairs on the boat as it rained non-stop, but repair we did. Cracks in the ceiling were opened up and filled, wood was re-varnished and gleamed like golden syrup in the rare moments of early spring sunshine. De-rusting and re-painting , sanding sanding sanding.

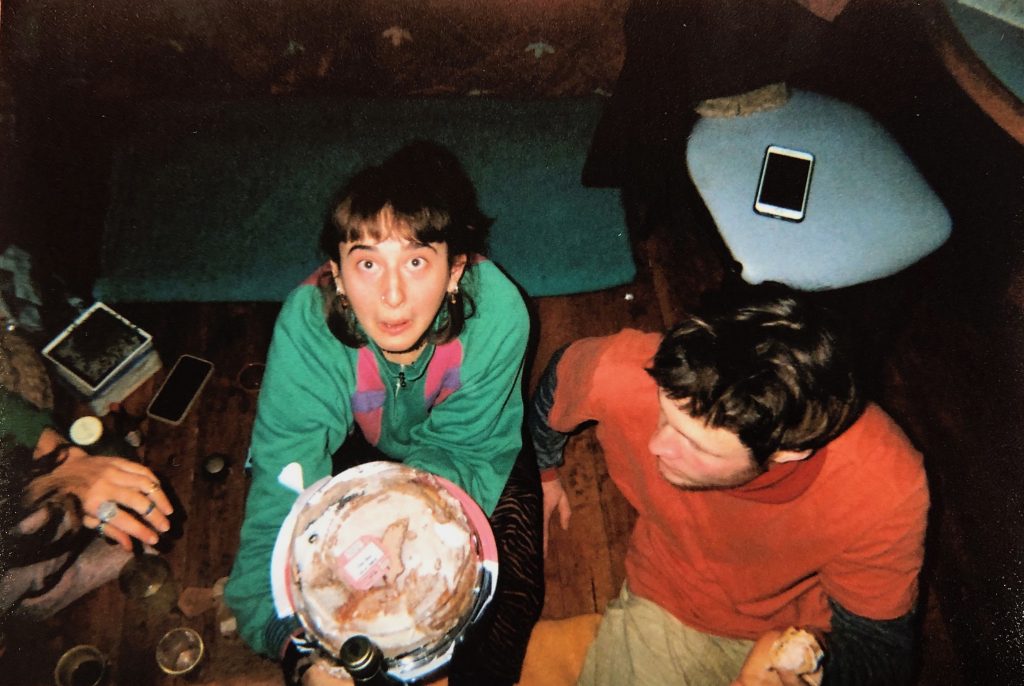

On the 17th of April we had our first sail of the year. The wind blew gales of 20-25 knots and the waves were choppy, rocking the contents of the cupboards, and vegetables from the last big dumpster dive onto a pile on the floor, a bilge salad of all my books, soft bananas, and a parsley plant. It was exciting and a reality check at the same time. We seriously needed to sort the boat out, and get our sea legs back. That night we squashed 6 people into Constanzes 2 seater Peugeot, with Tonio ‘playing’ the trumpet on the front seat, made our way back to Douarnenez for a feast of strawberries, mushroom leek and parmesan spaghetti and a big salad, all courtesy of the bins at SuperU.

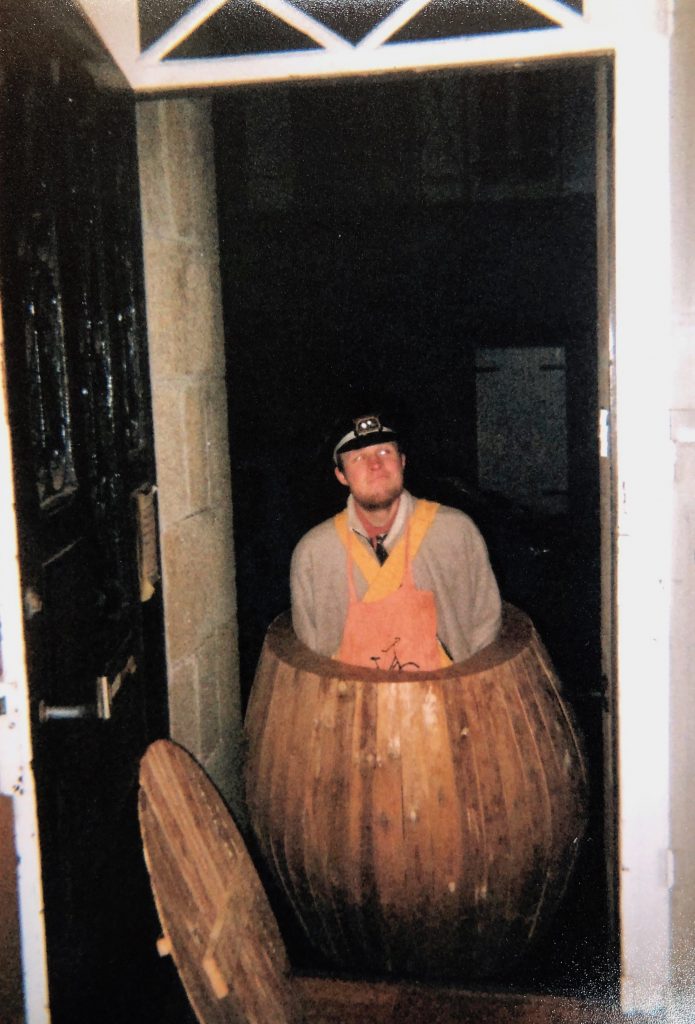

On a cold dark February night

A barrell was walking upright,

Belly full of whiskey, he'd dance and he'd kiss me

What a spirit what smokey delight

Then came the last days in Douarnenez. Suddenly I was all too aware of the comfort that the trees and rocks and shops that we saw every morning had brought me through the winter. Waking to different landscapes out of the window every morning felt far away and intimidating, and I wanted to hold on very tightly, to the land under my feet, my new friendships, the luxury of a bathroom!

Just before everything changes, the present seems to slow down and intensify, I experienced those last days as though through a magnifying glass. Joyous, larger than life, sometimes manic and stressful but all marvelous expressions of what had grown since our arrival in late September last year.

Constance, Soraya and I spent many evenings sharing songs by fire, oil lamp and moon light, laughing into the quiet night at the outragious accents and clashing harmonies we sang.

Finally on Sunday the 21st April, we left at midnight. Constanze was there, crying into the wind, waving tissues and playing dramatic Opera music. As the lights got smaller and the wailing of Italian heartache dissapeared behind, Atlanta rocked out of the bay and started sailing south under a full moon, just as we’d dreamed of nearly 3 years ago.

Leave a Reply to Jürgen Leicher Cancel reply